Asset Framing: The Other Side of the Story

Trabian Shorters

BMe Community

Key Takeaways:

Discover the psychological and cultural power of narrative.

Explore why deficit-framing sabotages equity and how to find smarter solutions.

Learn how to apply asset-framing in communications strategies.

Breakout Notes:

To a packed room, crowded with people standing and sitting and perching on window sills, Trabian Shorters describes a cognitive error case study — the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation made an investment in smaller classes and smaller schools following data showing a disproportionately high number of students do better in smaller schools. Dozens of orgs laid out causal explanations. It made sense and the data confirmed it.

But they were all wrong.

The same data showed that a disproportionately high number of students also do worse in smaller schools.

So, why was this reputable, fact-driven org, with the help of others, able to make a billion-dollar error without even knowing they had done it?

Facts vs. Narrative

Research psychologist, Daniel Kahneman, says Shorters, is the Einstein of this space. Kahneman won a Nobel Prize for his research revealing why we are fundamentally incapable of making unbiased decisions on any level.

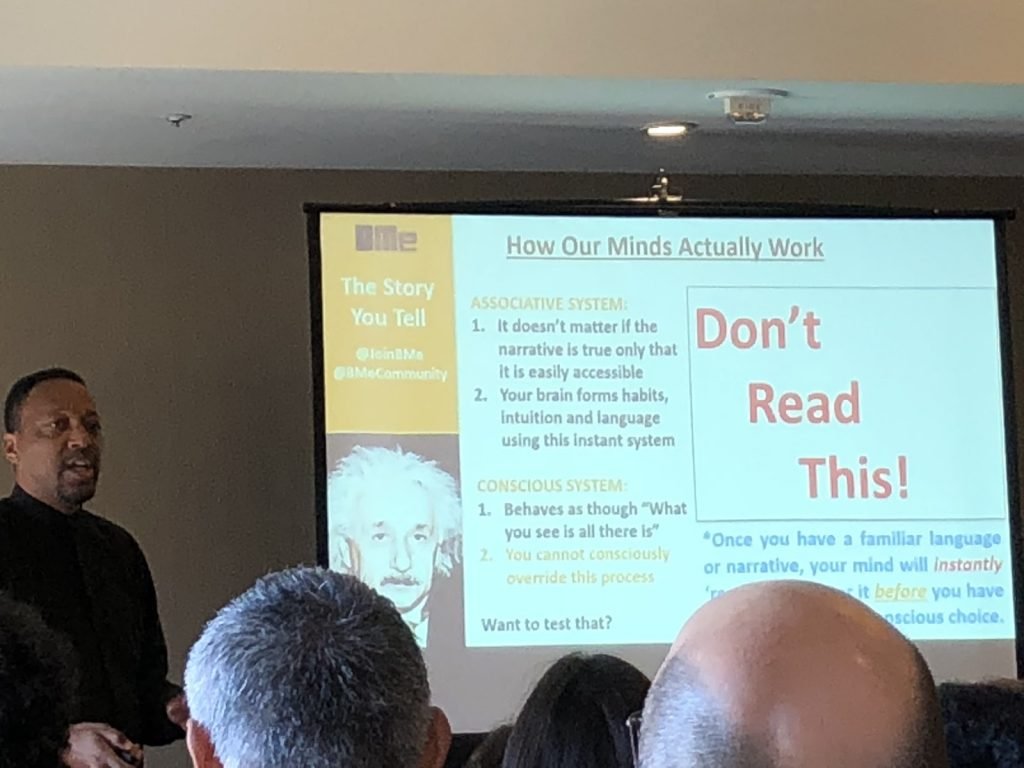

We have two systems in our minds:

First, the associative system, which is super-fast, has a habit of instantly forming narratives, and does 95% of our mental processing before conscious thought.

Then, our conscious mind, which interprets the world and makes decisions based upon what our associative minds make available.

That’s why when you’ve made a decision to buy a car, suddenly you’re seeing that car everywhere. Did everyone suddenly run out and buy “your” car before you did? Nope. It’s just in your narrative now, so your associative mind primes your conscious mind to see what has always been there.

Your brain is always trying to draw causal lines between events that happen in proximity. Like the relationship sports fans draw between defeat and not wearing their special lucky sports shirt.

Your mind is prone to disregard facts that aren’t relevant to the narrative your mind is building. Paying attention is effortful, so your conscious mind engages as little as necessary. The associative system accounts for 95% of your thinking.

Your associative mind doesn’t care about truth — it cares about speed and reflexively uses whatever information is most available to it.

Can you look at this image and not follow the instruction? If you can, you’re that rare person who can operate without bias.

Yeah, thought so.

Cognitive errors are everywhere. Since Google’s algorithm is also associative, it is great at revealing society’s unconscious but consistent associations. So-much-so that in 2013, researchers found that Google.translate flipped the genders when asked to translate “she is a doctor, he is a nurse” from English to Turkish and back again. A different study that same year found that Google Adwords would show crime-related ads more often if you searched for an “African-American sounding” name. Hopefully they’ve fixed these, but Google is set up to give results based on our most common associations. So this is less about condemning the software and more about how the software is prone to reveal our cultural narratives in order to give us what we’re most likely searching for. Even today, just type “boss” into Google image search and see what you get.

Narrative is a form of cultural grooming. In all societies, stories are how we reinforce the beliefs that our tribes live by. This is why politicians construct narratives before going to war. If the narrative is strong enough, we will put our lives on the line for it.

Shaping the Narrative

Shorters asks for a show of hands in the room if common stats — like black poverty is high — sound familiar. He then asks for people’s familiarity with an opposing stat. Everyone was familiar with the negative stats but not the positive ones. Nobody is familiar with the black-owned business rate, while everybody seems familiar with the unemployment stat.

It’s easy to tell the story of black and brown people in deficit, as a failure or a threat, in detail. But nobody can tell a detailed story about the successes and contributions of black and brown people.

Speaker asks us, in pairs, to look at each other intently and think about everything that is wrong with the person looking back at you. Everyone laughs; nobody wants to do it; it is extremely awkward. Nobody wants to define each other in the negative. So, why do it with communities?

To define someone by their challenges is the definition of stigmatizing them. But very often in our work, that’s what we do, and there are real cognitive consequences for that.

There are far more black kids doing well than not, but the imagery we see so often is of black failure, so our associative mind treats that imagery as the norm thought it is far from it.

We talk about solving systemic challenges, but Shorters says that the way we are defining the population makes it harder for us to do systems analysis. The CDC says that black fathers are the most engaged with their children daily in America, but the absent black father narrative blinds us to this reality, the same way that you were blind to seeing other cars that looked like yours until you thought about buying a new one.

Years ago, there were at least 110,000 millionaire black households in the US. Young people in black and brown communities are often aspiring to be entertainers or sportspeople. That’s maybe 4,000, 5,000 of the millionaire class. The kids might want to know that 95% of black millionaires don’t make it that way. Otherwise, they too will be blind to opportunities sitting right in front of them.

Your brain automatically creates associations, and if you’re just looking at the deficits, you’re missing half of the opportunities to make impact.

The Better Way of Thinking: Asset Framing

First, let’s define deficit-framing. It means defining people by their problems.

By comparison, asset-framing is defining people by their aspirations and contributions before exploring their deficits. It assumes that kids have value before the nonprofit shows up.

Mission and values statements can often contain mountains of deficit-framing. “We help at-risk youth in high-crime neighborhoods,” etc. Asset-framed, “We help young people overcome obstacles and achieve their dreams.”

The asset-framed narrative says, we want to help the kid achieve their ambitions. The deficit framed one only says, this kid has problems.

Speaker asked us to talk about nonprofits we admire and how it made us feel to describe their work. Then he asked us to say how we feel when we use the buzzwords like “at-risk” that are common in nonprofit mission statements.

The cognitive dissonance is that we like the orgs, but we’re using words by default that don’t make us feel good.

Why did we use the words? Because we’re trying to emphasize a crisis, because we need donors to know things aren’t good. But asset-framing doesn’t ignore challenges. It’s not about avoidance or substitution. It’s more accurate to introduce a young person by their aspirations and contributions before mentioning their challenges than it is to sum them up as an “at-risk youth.”

When we label a kid “at-risk”, your brain associates “at-risk” with the “youth”. When it’s time to do systems analysis, your associative mind defines the kids as the problem.

There’s also the hero story: our mission statements usually frame our organizations as a hero, so that leaves a hole for the villain, which our brain will fill in with the “beneficiaries.” Your brain wants narratives and will build them, instantly, without you.

Over time, framing things in the deficit creates cynicism and eats away at hope.

One of the benefits of asset-framing is that when you state someone’s aspirations, your brain instantly associates them with worthiness. It becomes much easier to see that the problem is not the person but situations and systems that block their worthy aspiration.

Freud said that “narrative, not facts, are the source of our judgment.” There are good guys and bad guys. Reshaping your narrative will literally let you see things that you could not see before.

One of the things that helped with marriage equality was to define gay and lesbian couples by their desire to be together. They talked about the things they had been through together — illness, kids, all of it — and how all they wanted to be able to do was get married to honor this commitment. This was a total pivot on the 50 years of defining these couples as oppressed.

Talking about their aspirations redefined the conversation.

Crisis narratives — the thing with them is that they trigger the survival part of your brain. That’s why they grab attention. But then, you set a narrative internally about getting away from it. It registers as threatening. You subconsciously set survival goals for that crisis narrative.

Equity – According to psychologist, Jonathan Haidt, if you have a liberal-leaning personality then you associate equity with “inclusion” but if you have a conservative leaning personality, you associate social equity with fairness. When we leave out the story of people’s aspiration and contributions, it seems unfair to give opportunities to someone who has no aspirations and makes no contribution. It doesn’t make intuitive sense.

If you remember nothing else, remember: Defining people by their challenges is the definition of stigmatizing them.

These notes were captured by The Communications Network and have been reviewed by the presenters. ComNet18 Breakout Session notes were made possible thanks to the generous support of the Kalliopeia Foundation.